Content Pruning: What People Get Wrong About It and When It's the Right Move

It's much harder to win the SEO game these days with bad or mediocre content.

In most verticals, the bar is simply far higher to clear than it once was.

You can't just throw up the same "me too" page as everybody else, point a bunch of links to it and expect to rank. At least not consistently.

And based on the helpful content signal, existing bad or mediocre content you may have previously published can also weigh down the rest of your site. Even if you otherwise might have plenty of other content that both meets and exceeds your users' expectations.

If you've found you've been negatively affected by recent algorithm updates or just aren't getting the traction in organic search you once were, you have several options to try and reverse things.

One of those options is content pruning.

Content pruning is exactly how it sounds. It involves outright removing content from your site that either isn't performing the way you want it to or doesn't meet user expectations in a clear enough way.

But is it the right move for every site?

How do you know what to get rid of and what not to get rid of so you don't make a bad situation worse?

That's what I'll cover today.

You'll learn:

-The Most Common Myths About Content Pruning

-How to Assess What To Prune

-A Quick Summation of the Process in 5 Steps

You should get particular value out of this if you don't already regularly prune content and have never gone through an exercise like this before.

Let's get started.

Common Myths about Content Pruning And When It Makes Sense

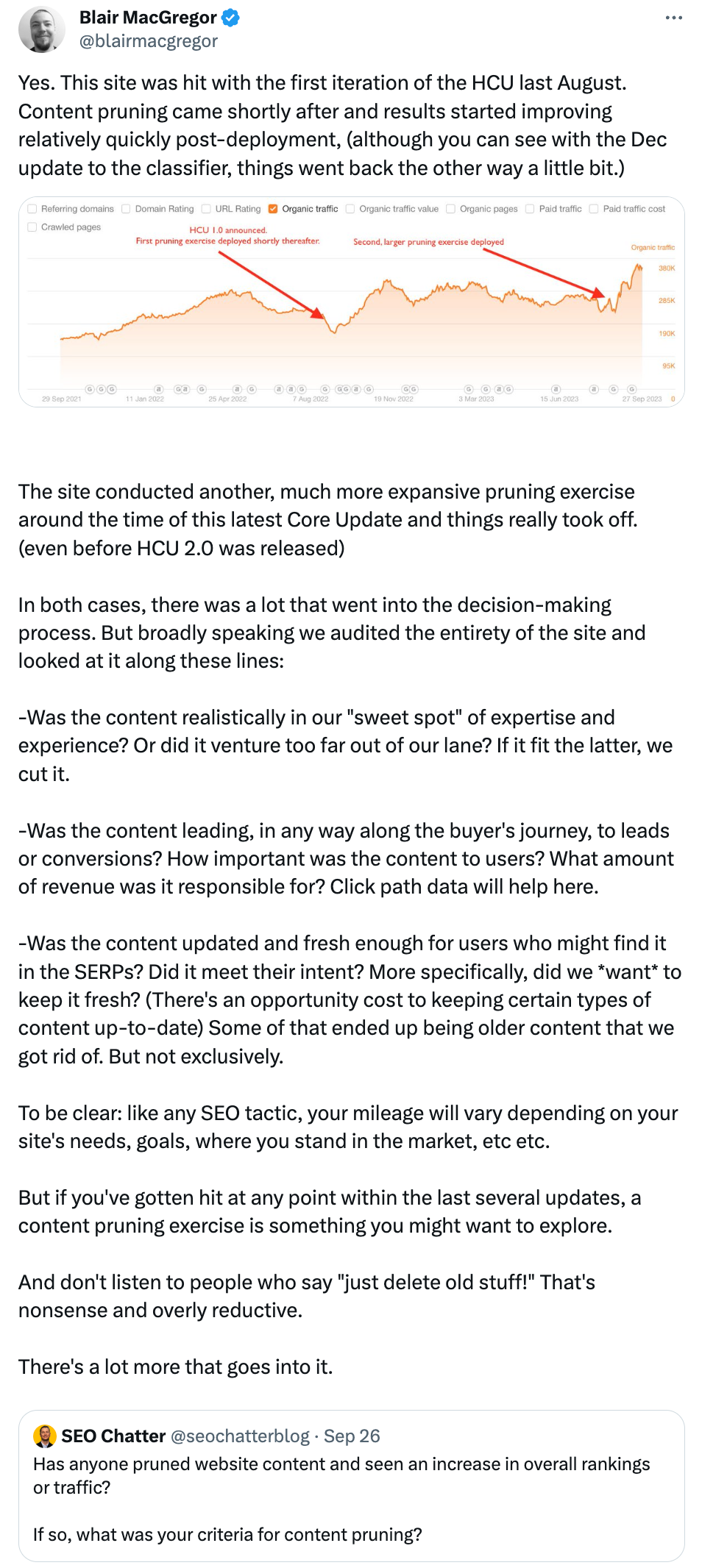

A few months ago, someone on Twitter asked publicly about content pruning: specifically whether or not anyone had seen demonstrable performance gains after doing it.

I spoke briefly about my experience doing this with Annuity.org and some of the positive results we saw, at least at the outset:

The interesting thing about content pruning over the last year is the exposure it's gotten from non-SEO or marketing outlets.

Red Ventures' CNET, which had already taken a beating for publishing AI content at scale (without disclosing it publicly) while at the same time conducting rounds of layoffs of editorial staff and supposedly breaching editorial firewalls, was criticized for its removal of old articles as part of a content pruning exercise its SEO team had apparently taken on.

Gizmodo, in this piece, implied that this was part of some sort of wider diabolical plot by CNET to somehow "game Google search."

In practice though, that wasn't really the case, as Cyrus Shepard pointed out at the time:

Lot's of hoopla about CNET removing "old" articles

— Cyrus SEO (@CyrusShepard) August 10, 2023

But that's not exactly what's happening...

From CNET's internal memo, this is how they think about Content Pruning: pic.twitter.com/IccOMV6hA1

The truth is there's nothing morally wrong with content pruning. After all, no one wants to read outdated or otherwise unhelpful content.

At best, it's annoying to stumble across; at worst, it can be actively harmful to readers when weaponized for the purposes of disinformation. (So much so that news organizations have gone out of their way to more distinctly label outdated content to help prevent misinformation.)

Some might think the solution is to just keep your content updated. And in an ideal world, that's usually true.

But there are plenty of reasons why it's not always possible to keep content updated:

- Brands don't always have the internal capacity to keep content evergreen in light of all of the other things that need to get done. In my last post, I talked about content debt within the context of opportunity cost. The idea is that as sites scale their content production, the cost of keeping that content up-to-date becomes a bigger and bigger price to pay. Depending on the size of your team, it can hamper your ability to create new content if you don't have an adequate enough plan to account for the maintenance. And you may find yourself in a position where updating problem content is simply more work than just getting rid of it. Using external content vendors may solve that dilemma to a degree. But they too have to be managed. So oftentimes, problem content lingers on-site because nobody wants to deal with it. Especially if the content isn't integral to the business: either it's an ancillary or complementary section of content that has lower commercial value. And that's when you can get into trouble.

- They don't know the content still exists! This is more common than you might think, especially with enterprise sites that have thousands (millions?) of pages and may have whole sections and categories of legacy content that the current team managing the web site isn't aware of. This kind of thing happened all the time when I was at digital agencies working with enterprise brands; even those with dedicated SEO support.

- It's content that they don't stand by anymore for whatever reason. Maybe the site's gone through an evolution editorially and doesn't hold up well compared to what you publish now. For instance, Drugwatch, a health informational site I worked on that monetized through mass tort leads, used to have a whole section dedicated to vaccines and what they called "vaccine-related injury." The content, on balance, was informative and non-hyperbolic. But you can imagine the kinds of sites that used to link to it, some of which are still there if you look up their backlink profile in your SEO tool du jour. And this was in 2017 and 2018 before COVID! (It was thankfully removed prior to the pandemic.) Maybe you don't have the same issue with content that could be used as a "honeypot" for bad actors to link to. But it's still not stuff you stand behind anymore.

- It's what we might traditionally call "junk content" for SEO purposes. Outdated tag or category pages, duplicate product pages, location-based content that doesn't add any kind of unique perspective and looks more like a doorway page, etc. Even just static content pages that talk about the same thing. The stuff that serves zero value to anyone. Obviously, this is the kind of content that's the easiest to get rid of.

A few other prevailing myths I've seen out there about content pruning that I'll fact-check Snopes-style:

Claim #1: Content pruning will lower my overall site authority. Doesn't more content always = more traffic?

Not necessarily and no.

Obviously, it's true you may lose traffic in the short term by removing content. What you're banking on though is that removing what's very likely considered unhelpful content will help improve the perception of your site as a whole. In Google's words:

Any content—not just unhelpful content—on sites determined to have relatively high amounts of unhelpful content overall is less likely to perform well in Search, assuming there is other content elsewhere from the web that's better to display. For this reason, removing unhelpful content could help the rankings of your other content.

The bad stuff has the potential to serve as an anchor weighing the rest of your site down. That's reason enough to address it.

Claim #2: It's all about just deleting old stuff.

False. You should never remove content merely because it happened to have published a while ago. Publish date is only one data point among many to analyze when conducting a content pruning exercise. Old content often still has plenty of value to audiences who are searching for it, not to mention the benefits from any links that have accrued to the content over time.

Claim #3: It’s as easy as just getting rid of content that hasn’t generated any traffic.

Also false for the same reason: traffic is merely one data point. In reality, the content may also simply need more time to rank. We know SEO is a long-term play. And if your content was only published, say, a month ago, it could just be the case that Google has yet to contextualize the new content you've written relative to what else is out there on the topic as well as what you've previously produced.

Claim #4: Once you've pruned the content, that's it. There's no bringing it back.

False. It's absolutely possible to un-publish the content, work on it and then re-publish it later on once you've had a chance to give it the attention it deserves. For example, it very well could be the case that new topics might be on your 5-year roadmap but that you don't have the resources to devote to them right now. Keep that in mind.

Claim #5: You can just keep the content on-site and no-index it in the same way you would no-index paid landing pages etc.

It's possible to do this. But I wouldn't advise it if it's content that's already been indexed and has accumulated links. After all, if it remains on-site in its current (non-updated) form, it's still not any more helpful to users than it was already. If you don't stand by it in its current form and you can't or don't want to update it, you should get rid of it.

Plus, no-indexing doesn't impact whether the page is crawled or not. And in an era where Google's becoming far pickier about what ultimately gets indexed in Search, crawl budget has become something even non-enterprise sites are starting to pay attention to. So if there's content that has little benefit to users, it's best to get rid of it so that crawlers can focus on your high-value content instead.

How Should I Assess What to Prune?

There's no single vector by which to judge whether a group of pages should be pruned or not.

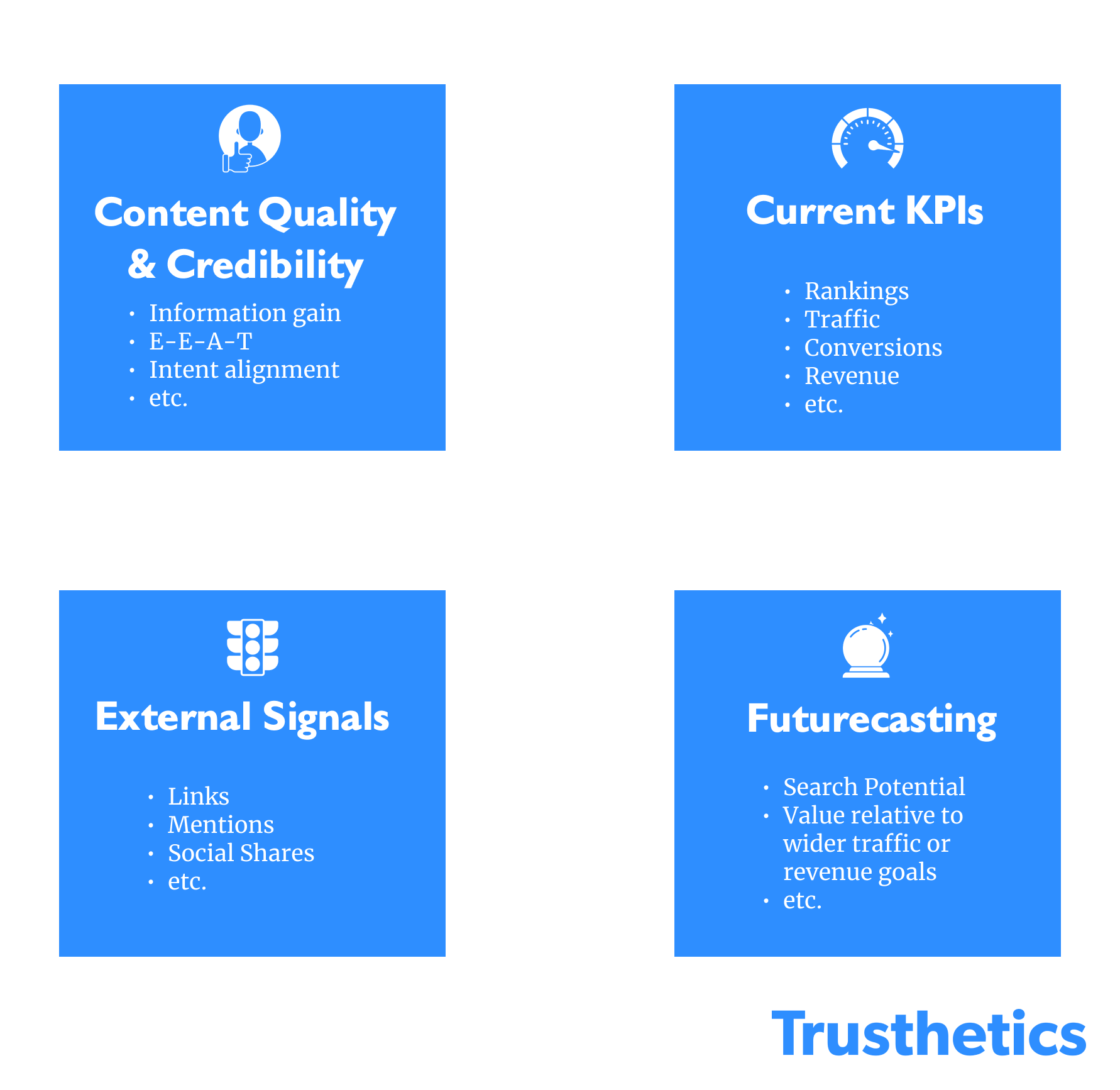

Instead, one way to look at it is to consider questions in four different buckets:

Content Quality (Information gain, E-E-A-T, intent alignment)

Information Gain

Does the content add something to the collective body of knowledge that already exists on the web for the page's topic? Are there insights, statistics, data points that you're including that nobody could find anywhere else? Or are you just producing the same kind of page and regurgitating the same information everyone else is?

Most of the standards I talked about in the last post about content expansion fall into this bucket.

Freshness

If the queries you're targeting with a certain piece of content convey a high degree of freshness on behalf of the user, then you need to meet that expectation.

Anyone who publishes content in the finance space, for instance, knows that rate content (e.g. mortgages, credit ratings etc.) has to be kept up-to-date or users will lose trust and quickly click away.

If the content is out-of-date and it isn't something you want or even can update (in the case of an old news story or a page about 2019 tax information), does it serve as a kind of historical record of a given time period? Would somebody looking up that information for research purposes find it valuable? Or is it more likely to confuse someone who might come across it in Search? If it's the latter, it's probably a good candidate to be removed.

E-E-A-T and Reptuational Signals of the Creator

What are the credentials of the author and/or whomever else is on the Editorial byline? Are they qualified to write this piece? Or should you find someone with better credentials who can re-write or otherwise update it? Especially if the author is someone who doesn't write for you anymore.

Intent Alignment

Does what you've written on the topic align with the kind of information the user's looking for? If, for instance, the user is looking for a specific question to be answered, are you answering it within the first few paragraphs or are you waxing poetic for the sake of it? Remember, content quality does NOT always mean length.

Additionally, is the content written with respect to where your target user currently sits in the journey? Or are you, say, writing heavily transactionally-oriented copy when the person's actually just looking for information?

Proximity to Core Audience

This is a lot of what I talked about in the last piece. Does the content in question tie back to your core audience? Would they find it valuable?

Or was it written just because you thought you could leverage your domain authority to rank for it?

Topical Authority

The more you've consistently written about a topic, the more likely it is that Google sees you as authoritative for it.

Publishers used to be able to slowly inchworm their way into a new topic by creating a few pages at the start and leveraging their domain authority to rank quickly. Much like a startup, they'd deploy content in a lean startup kind of way. "Just ship it and then add to it later."

That doesn't tend to work as well nowadays.

Take a look at sections of content that might otherwise not be as fleshed out as the rest of your site. Can you dedicate resources to expanding those sections and making them as good as the other sections that are fully fleshed out? If not, it might be worth getting rid of.

Editorial Voice

This is a big one that I don't see a lot of people talking about.

If you've been publishing for a long time, your content's probably gone through an evolution: not just in terms of quality but perhaps even stylistically, in terms of tone of voice, etc.

For example, Annuity.org began life targeting the secondary annuity market: people who wanted to sell their structured settlements and other payment streams in the form of an annuity for immediate cash. The site barely referenced the idea of purchasing an annuity for retirement. In fact, in going back and auditing some of the older content in 2020, we uncovered a number of references to the primary market in an inaccurate or dismissive way. The Editorial voice had clearly changed with the content's expansion. But the previous content still had the old tone and only the old audience in mind. So we either re-wrote that content or got rid of it.

If you have content that fits that description, can you re-write it? If not, it's likely a good candidate for removal.

Current KPIs (Rankings, Traffic, Conversions, Revenue)

The key is to get a sense of where your content stands now relative to where it might've been in the past.

Has it had any kind of traction in the last 18-24 months? Or has it been basically DOA since it was published?

What have the traffic cycles been like? Are there patterns in GA/GSC that you can pick up on?

Is this content that contributes to your primary conversion or revenue goals in any way? If you analyze the most common click paths your converting users take, are these pages part of it?

External signals (Links/Mentions/Social shares)

Oftentimes, if the content you're looking to prune has never generated any kind of traction, it likely hasn't generated much in the way of links and social shares.

But that isn't always the case.

When we made the decision to get rid of large swarths of the personal finance content we had published, not only were many pages ranking in high positions for a variety of keywords but many had also passively acquired some great links from highly authoritative sources. Those are always tough to give up on.

But at the end of the day, consider this: even if they're from reputable sources, if they don't serve your audience in a meaningful way, how meaningful are they to your business as votes or endorsements?

Futurecasting (Search potential)

The other part of the equation to take into consideration is what the potential for future success actually is.

Is the new content serving a growing market? Has there been any demonstrable traction you can point to to prove that the metrics are trending in a positive direction? What does the competition look like?

Ideally, you'd have considered these factors before writing the content. But maybe your plans have changed. Or maybe external circumstances (e.g. search demand) have to the point where it no longer makes sense to be writing this content.

In any case, it may be worth conducting a traffic forecast (or re-visiting the one you did previously) to determine, to the extent that you can, what you could reasonably expect from the traffic

Or is it the case that, even if you could re-write the content to the point where it was best-in-class, it wouldn't do much for your business? In the latter case, that might be indicative of something you'd want to get rid of.

Content Pruning: A Quick Step-By-Step Summation of the Process

In terms of the actual nuts and bolts of the data analysis and collection part of this, there's no "one-size fits all" approach. But here's how I've done this sequentially in the past:

- Assuming you're looking to prune content as a response to losses in traffic, you'll probably first want to complete a broader traffic-drop assessment if you haven't already. (For one, it'll allow you to better determine whether the drops in traffic represent a content quality issue or something else. Secondly, you'll need the traffic metrics anyway as a data point regardless in order to help determine whether something should be pruned.)

- Determine when site-wide traffic first started to drop, then decide on a statistically-significant enough sample size to compare before and after the drop. Make sure to layer on or annotate the time periods where major algorithm updates (Core, HCU) took place to pinpoint any patterns. You should also account for seasonality, if you know that's something that regularly affects you.

- Export the most relevant KPIs by URL for each time period, categorized by theme or cluster. This will be different for every site but could include things like:

- Traffic metrics (Sessions, Users, New Users from GA) at the page level

- Search visibility metrics (Clicks, Impressions from GSC) at the page level

- Number of referring domains/backlinks tied to each page. This is another relevant metric, since you'd obviously like to avoid having to 404 or re-direct any content with authoritative links pointing to it.

- Conversion and/or revenue data associated with each page (Leads, MQLs,/SQLs, Sales, Customers, RPM etc) - You're trying to answer the question of "can you afford to get rid of this content?"

- Publish/Update date of each page

- Authors/reviewers tied to each page

The complexity of your data and the number of KPIs will dictate whether it's worth comparing everything in one sheet or using pivot tables.

- Make the decision to either keep, re-write or prune each page based on the criteria we talked about earlier. For pages (or groups of pages) that you know need to go, you don't need to do anything else. Other content might be more of a judgement call. I found it helpful to include a notes column as well, not just to justify to higher-ups in the company my rationale for a decision on a particular page but also to help me go back and come to a final decision later for pages that I was on the fence about re-writing or getting rid of.

- For the content you've earmarked for removal, choose a relevant page you're keeping on-site to 301 the outgoing page to, if possible. If not, re-direct the outgoing page to the home page. Since we were working in WordPress, we chose to un-publish the pages we had marked for removal and keep them as drafts in the backend in the event we decided to re-visit them. You might want to do the same.

Takeaways

Low-quality content on a site can negatively affect the entirety of how that site performs in Search: even weighing down performance of the good stuff. Content pruning is one potential solution to this (albeit not the only one) if it's not worth updating the low-quality content.

Contrary to some beliefs, content pruning is not just about deleting old stuff or an indication of a flawed SEO strategy. Instead, it's a nuanced process that involves considering the quality, relevance, and performance of content in the context of not just current SEO trends but your own publishing goals as well.

Use the four buckets in the chart above (content quality, internal KPIs, external signals and futurecasting) as a way to assess whether something should be gotten rid of or not.